Mouse Study Offers Hope for Gene Therapy Against Parkinson’s Disease

THURSDAY, Nov. 4, 2021 (HealthDay News) -- An experimental gene therapy to boost the effectiveness of the Parkinson's drug levodopa yielded promising results in mice, researchers report.

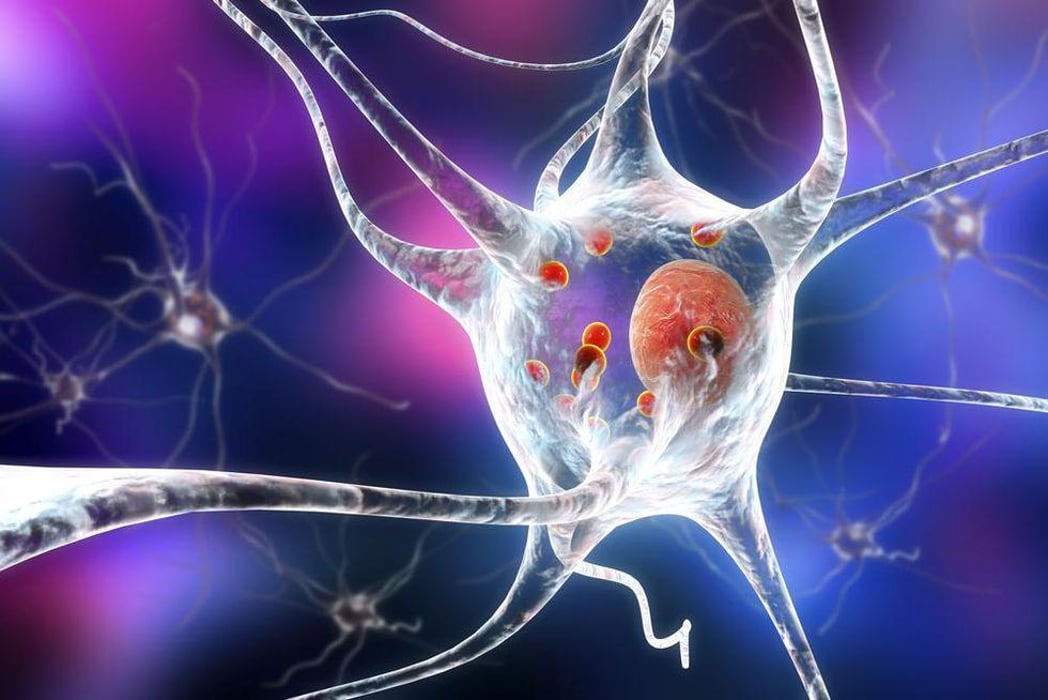

As the loss of dopamine-releasing neurons advances in late-stage Parkinson's, levodopa is less able to ease movement problems caused by the disease, which is a progressive disorder of the nervous system.

But a Northwestern University team found that gene therapy targeting the brain region in mice where those neurons are located significantly increased levodopa's benefits.

The gene therapy did this by restoring the neurons' ability to convert levodopa to dopamine, according to the researchers. However, animal research does not always pan out in humans.

Along with their findings about the gene therapy, the investigators offered new insight into why dopamine-releasing neurons are lost in Parkinson's disease patients.

In mice, the researchers found that damage to the mitochondria (the power plants) in dopamine-releasing neurons triggers a sequence of events that resemble what happens to brain circuits in Parkinson's disease.

The findings may help identify people in the earliest stages of Parkinson's and lead to therapies to slow disease progression and treat late-stage disease.

"The development of effective therapies to slow or stop Parkinson's disease progression requires scientists know what causes it," said study author D. James Surmeier, chair of neuroscience at Northwestern's School of Medicine.

"This is the first time there has been definitive evidence that injury to mitochondria in dopamine-releasing neurons is enough to cause a human-like Parkinsonism in a mouse," he said in a university news release.

"Whether mitochondrial damage was a cause or consequence of the disease has long been debated," Surmeier noted. "Now that this issue is resolved, we can focus our attention on developing therapies to preserve their function and slow the loss of these neurons."

The study also provides a model of Parkinson's disease before symptoms appear.

"This new 'human-like' model may help us develop tests that would identify people who are on their way to being diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in five or 10 years," Surmeier said. "Doing so would allow us to get them started early on therapies that could alter disease progression."

The findings were published Nov. 3 in the journal Nature.

More information

The Parkinson's Foundation has more on Parkinson's disease.

SOURCE: Northwestern University, news release, Nov. 3, 2021

Related Posts

Algunos comestibles de marihuana imitan a los dulces, lo que aumenta el peligro de los niños

MARTES, 19 de abril de 2022 (HealthDay News) -- Los comestibles de marihuana que...

Study Confirms Rise in Child Abuse During COVID Pandemic

FRIDAY, Oct. 8, 2021 (HealthDay News)– Physical abuse of school-aged kids...

Another Study Finds Vaccine Booster ‘Neutralizes’ Omicron

THURSDAY, Jan. 20, 2022 (HealthDay News) -- If you need more proof that a third...

Serotonergic Antidepressants in Pregnancy Not Tied to Neonatal Seizures

THURSDAY, May 12, 2022 (HealthDay News) -- Following adjustment for confounding...